Software Estimations: The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly

Software Estimations: The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly

🎭 The Controversy

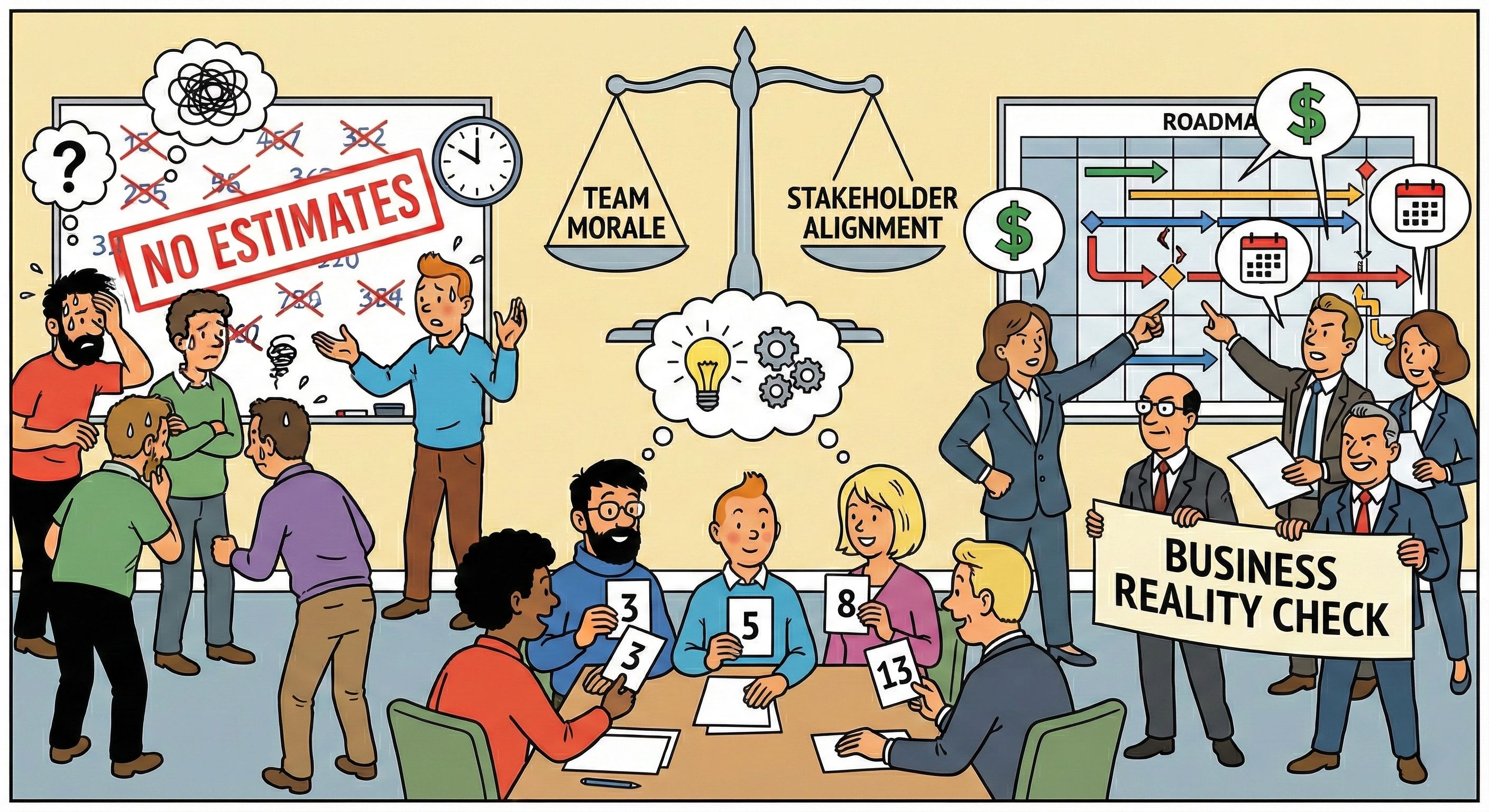

Software estimation sits at the heart of one of the industry's most heated debates. And it's not just an abstract industry issue—in my personal experience across countless projects and initiatives, estimation has been the hot topic that inevitably surfaces in every team discussion, sprint planning, and stakeholder meeting. It's the conversation that never goes away.The #NoEstimates movement, which gained momentum in 2012 when agile coach Woody Zuill started using the hashtag on Twitter, argues that estimation often wastes time and can be counterproductive. DHH, creator of Ruby on Rails, bluntly states that "software estimates have never worked and never will," arguing that smart programmers have tried for decades and consistently failed.

The controversy isn't unfounded. Software estimation is full of challenges: loss of credibility with customers, internal team friction when management over-promises, poor morale from excessive hours, and low-quality software when developers rush to meet deadlines. The debate is so divisive that experts are often reluctant to even discuss it publicly.

But here's the uncomfortable truth: we're terrible at estimating because of fundamental human psychology. Research by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky identified what they called the planning fallacy—our tendency to underestimate the time, costs, and risks of future actions while simultaneously overestimating the benefits. This isn't a software problem; it's a human problem.

Consider these cognitive biases that sabotage our estimates:

- Optimism Bias: We assume we won't run into complications that will cause delays, expecting the good to happen rather than planning for realistic scenarios

- Planning Fallacy: People underestimate how long tasks will take despite knowing that similar tasks have typically taken them much longer in the past

- Illusion of Control: We overestimate our ability to control events and outcomes we demonstrably cannot influence

- Dunning-Kruger Effect: Unskilled individuals overestimate their abilities, while experts underestimate theirs

The nature of software development amplifies these biases. As Donald Rumsfeld famously said: "There are known knowns, known unknowns, and unknown unknowns." The reason we rarely know how long a task will take is simple: we've never done it before. Once software development becomes routine enough to estimate accurately, it typically becomes a product or service you can just buy rather than build. Thus, most software work involves solving novel problems.

Steve McConnell, a software estimation expert, points out that many #NoEstimates comments demonstrate a lack of basic software estimation knowledge, and that people often confuse estimates with targets or commitments (and I can picture half of my colleagues and friends nodding vigorously right now—we've all been there). An estimate is a probabilistic assessment based on current information; a commitment is a promise to deliver by a specific date. Confusing the two creates unrealistic expectations on both sides.

💼 Why Professional Software Requires Estimates

Despite all the challenges outlined above, estimates remain necessary in professional software development. The question isn't whether to estimate—it's how to estimate responsibly.

Business Reality Check

Customers want a general idea of how long tasks will take, and it's easier to sell a software solution with a fixed delivery time than to admit that the customer will simply get whatever the team can complete in the allotted time. We are all trying to create better predictability for our teams, customers, and internal stakeholders.

Beyond satisfying finance departments and external stakeholders, estimation serves critical functions for the engineering team itself. It's not just about producing a number; it's a mechanism for alignment.

1. Establishing Shared Understanding

The true value of an estimation session, like Planning Poker, isn't the final number—it's the conversation that generates it. When one developer estimates a task as a "3" and another as a "13," the resulting debate uncovers hidden assumptions, risks, and missed requirements. The principal value of estimating is the discussion among team members that takes place when they try to agree on a size, resulting in shared clarity from thoughtful and sometimes vigorous debate.

2. External Coordination

Software doesn't exist in a vacuum. Estimates help align marketing campaigns, support staff training, sales efforts, dependencies and other organizational activities with the delivery of new features. Without some level of predictability, these teams operate blind.

3. High-Level Decision Making

Executives need rough estimates (often called "t-shirt sizes") to decide which initiatives belong on the roadmap and which are too expensive to pursue. When determining whether to work on features, there's value in understanding the size of the work and the prioritization.

4. Better Cost-Based Prioritization

Understanding relative effort helps product owners make informed decisions about what to build next. A high-value, low-effort feature should probably jump ahead of a low-value, high-effort one.

While Agile emphasizes responding to change, it also values following a plan—the Agile Manifesto explicitly states "there is value in the items on the right," which includes the phrase "following a plan". The key is finding the balance.

🛠️ Tips for Better Estimations

If we must estimate, we should do it in a way that minimizes anxiety and maximizes accuracy. Here are best practices derived from modern agile methodologies and research.

1. Stop Estimating Time; Start Estimating Effort

Humans are terrible at predicting absolute time (e.g., "this will take 4 hours"), but we're surprisingly good at relative comparison (e.g., "this rock is twice as heavy as that rock").

Use Story Points: Story points represent a combination of effort, complexity, and risk, decoupling the work from individual developer speed and allowing the team to estimate the problem rather than calendar availability. Points aren't about time—they're about the size and complexity of the work.

Use the Fibonacci Sequence: The Fibonacci sequence (1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21...) reflects inherent uncertainty in estimating: as items get larger, the uncertainty increases, and the larger gaps between numbers force estimators to make more meaningful distinctions. By using a non-linear scale, you acknowledge that uncertainty grows as task size increases.

2. Choose the Right Technique for the Context

One size doesn't fit all. Adapt your estimation method to the project stage:

For Early Discovery: T-Shirt Sizing

When you have a massive backlog or are roadmapping, don't use numbers. Categorize items as XS, S, M, L, or XL. This avoids false precision and "analysis paralysis."

For Sprint Planning: Planning Poker

Planning Poker is a consensus-based technique where team members privately select cards representing their estimate and reveal them simultaneously, avoiding anchoring bias where the first person to speak influences everyone else. Research shows that the lively dialogue during poker planning improves estimate accuracy, especially for items with uncertainty, and being asked to justify estimates results in better compensation for missing information.

For Massive Backlogs: Affinity Estimation

If you have hundreds of stories, arrange them relative to each other on a wall or virtual board by complexity rather than discussing them one by one—it's incredibly fast and visual.

3. Estimate as a Team

Agile estimation should never be a solo activity performed by a lead developer or manager. Involving the whole team ensures that diverse perspectives are considered and exposes knowledge gaps—a senior developer might think a task is easy, but a junior developer might spot a dependency that adds complexity. This "wisdom of the crowd" leads to more realistic forecasts.

4. Separate the Estimate from the Commitment

A critical cultural shift is distinguishing a forecast from a commitment. An estimate is a probabilistic assessment based on current information; a commitment is a promise to deliver by a specific date.

Use Ranges: Instead of giving a single number, communicate uncertainty. For example, "We are 90% confident we can finish between 17 and 23 points this sprint."

Track Velocity: Once you have a history of actual delivery (velocity), use that data to forecast future dates rather than relying on gut feeling. Agile tools like Jira track story points, making retrospectives and estimate recalibration easier—teams can review the last 5 user stories with a specific point value and discuss whether they had similar effort levels.

5. Use Reference Class Forecasting

Reference class forecasting involves comparing the current project with similar projects completed in the past, plotting out how long each took, and then comparing the current task with all past outcomes. The most accurate benchmark for a task's time isn't your personal evaluation, but the time it has taken others to deliver similar outcomes before.

6. Break Down the Unknowns

The fundamental truth about work breakdown structure estimation is this: the only way to estimate with true accuracy is to implement the project. The cost of improving estimates grows exponentially with every layer of breakdown, but the benefits do not.

Instead of spending weeks perfecting estimates, focus on identifying the "known unknowns." If a story estimates to 8 or 13 points, it's too big for one sprint and needs to be broken down into smaller, more manageable tasks.

🎯 Conclusion - Finding the Balance

Let's be honest: software estimation is hard, uncomfortable, and often feels like a setup for failure. As engineers, we face the discomfort of looking someone in the face, saying "I don't know," and then standing our ground when they pressure us for certainty we cannot provide.

But here's what we need to remember on both sides of this conversation:

For Engineers: Your frustration is valid. The cognitive biases, the inherent uncertainty of novel work, and the pressure to commit to impossible deadlines are real challenges. But refusing to estimate isn't a solution—it's an abdication of responsibility. What you can do is be honest, educate stakeholders on what an estimate really means, and create a safe culture where you can estimate with the knowledge you have at that moment.

For Business Stakeholders: Understand that software isn't a commodity that can be precisely measured like building a house with standard materials and known processes. Every software project involves solving unique problems. When you pressure engineers for certainty, you're not getting truth—you're getting a number they know you want to hear.

The path forward requires mutual understanding and shared responsibility:

-

Foster Psychological Safety: Create an environment where engineers can give honest estimates without fear of punishment when reality proves more complex.

-

Embrace Commitment with Flexibility: Sometimes we need to make an effort to achieve delivery targets—ownership and commitment matter. But when challenges arise, the conversation shouldn't be "Why were you wrong?" but rather "What alternatives do we have?"

-

Offer Alternatives When Needed: When estimates prove optimistic, don't just work harder—work smarter. Can we adjust scope? Can we build in phases that remove pressure sooner? Can we deliver a smaller version that provides value while we continue developing?

-

Remember the Goal: Estimates exist to enable better decision-making, not to create false certainty. The conversation during estimation is often more valuable than the number itself.

It's hard to know when you'll finish when the path you'll take and the destination are both unknowns at the start of the journey. Focusing exclusively on getting estimates right often turns attention away from the real goal: delivering business value, enabling learning, and solving customer problems.

If all people involved in a development process share the same understanding of what an estimate is and how it can be used, the world becomes a place with less frustration, fewer developers feeling like they've failed, and better collaboration between engineering and business.

The bottom line: It's the developer's responsibility to be honest and make people understand what an estimation is and what it is not. It's everyone's responsibility to use that information wisely.

What's Your Experience?

Have you found techniques that work particularly well for your team? What challenges have you faced with estimation? Share your thoughts in the comments—I'd love to hear how different teams navigate this eternal paradox.

References & Further Reading

- #NoEstimates Movement Resources

- Planning Poker Guide - Mountain Goat Software

- The Planning Fallacy - Society for Personality and Social Psychology

- 17 Theses on Software Estimation - Steve McConnell

- Kahneman & Tversky on Planning Fallacy

- Software Estimation is a Losing Game - Richard Clayton

- Why Software Estimates Never Work - DHH

- Story Points in Agile - Atlassian